COPYING MASTERS

THEN MASTERING OWN ART

Prof. Khatchatur I. Pilikian

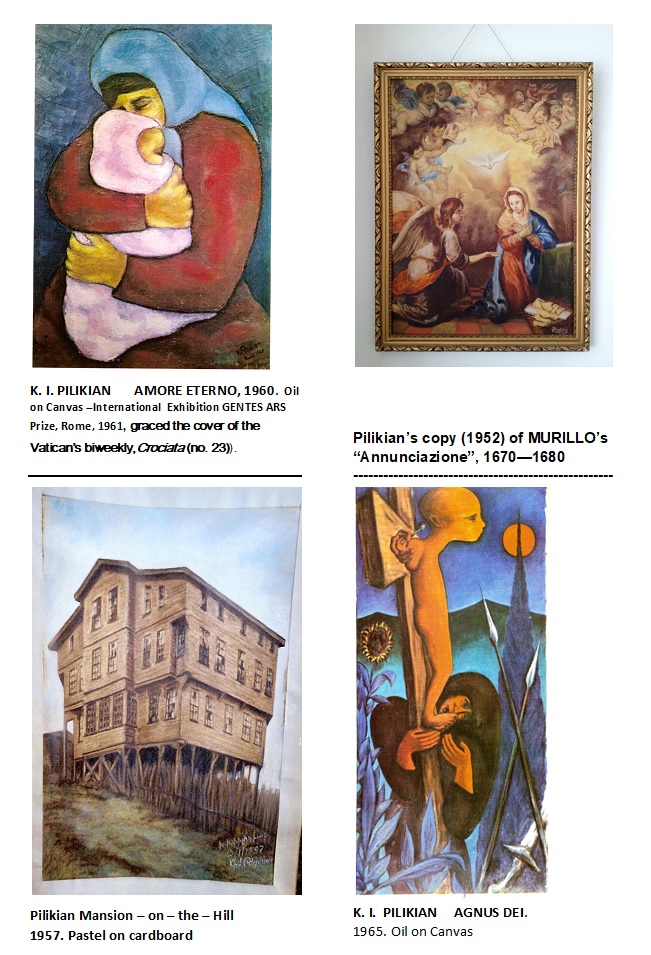

I was just becoming a teenager, in 1952, when we arrived in Beirut from Nineveh – Mosul with all my family, father, mother, three sisters (one, my twin) and a younger brother. My twin sister and I were enrolled at an Evangelical High school which was well accredited by the American University in Beirut. One sunny afternoon, coming back home from school I visited a local bookshop. There were, at a corner bank, post-cards of famous painter’s masterpieces. I bought a large post-card of Murillo’s Annunciation for my mother.

She loved it and challenged me saying “you are scribbling here and there with sketches and colours, let me see if you can reproduce this on a large canvas, then I will call you a real painter”. I did not answer with “I will try”. My courage nudged me to say ” I will do it, mother”. I worked during the summer recess. It was done. You should have seen my parents’ feeling of Eureka…

Few months later, in autumn 1952, I passed the tests and entered the Fine Arts Academy, enrolled in the early evening studio sessions. There we had a female nude — the one and only in town. The moment I entered the studio Mariam (her name) covered her body. The Professor of painting was quick to remind her ” Mariam, please uncover, the young man is officially permitted to sketch your nude figure”. From Virgin Mary to Mary the Nude, my journey into the world of art proceeded with a rabbit’s pace.

My mother, Tefarik, born in Khaskal-Izmit (Nicomedia), had survived the genocide and lived as a child with her mother. Her father Hagop was dragged to serve the Ottoman army as hard labourer (amele tabourou) in Jerusalem. Knitting to survive with her mother in Thessalonica, my mother was ‘found’ by my father when she was in her twenties. My father, Vahan/Israel, born also in Khaskal, survived the Der el Zor hell on earth in the Syrian Desert. As an orphan in Baghdad, he decided to find his childhood beloved come rain or sunshine. He did. They stayed together for over 65 years – now buried together in London (father 95, mother 87). Both parents had very beautiful voices – I have learned many songs first from them. I remember vividly my father’s singing to raise funds for the families of the Armenian soldiers fighting against the Nazis…

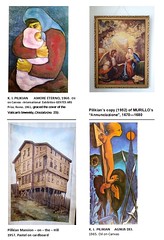

After copying Murillo’s Annunciazione, it was the turn of my father to ask me to reproduce from a unique photograph, a memento he treasured for more than a half century. It showed, in black and white, an impressive wooden mansion on-a-hill, in his and my mother’s birthplace, the Armenian village of Khaskal in Ancient Nicomedia. The picture was of ‘our ancestral mansion’, as my father called it. Not rushing with his loving request, my father, being a passionate believer in academic studies that he and my mother never had the chance to indulge in, he waited until my High School graduation in 1954 (with my twin sister), then my enrolment to the American University in Beirut – AUB. He waited for me to be a student of Architectural Engineering, only then to tackle ‘reproducing’ our ‘ancestral home’, albeit as a pictorial image. I tackled my labour of love during the Christmas and New Year 1957 festive days. I signed my copy of ‘our ancestral mansion’ on January 13.

As a child of ten, my father Israel-Vahan Pilikian had “helped” his own father Hovhanness, a master builder, to build the new family house his father designed and planned, in their home village, Khaskal, during 1912-1913. The village, mostly inhabited by Armenians numbering ca. a thousand, was not far away from the celebrated Armenian Monastery of Armash, in Izmit (ancient Nicomedia).

After the large and extended Pilikian family was driven away from the new paternal home, the enormous three story wooden building was confiscated by an officer of the Central Powers and used as army barracks. Surviving the bombardments of the Allied Powers, the Pilikian mansion was subsequently occupied by the Kemalist forces of nationalist uprising.

After the Great War, having survived the Genocide of the Armenians (1914-1918), Israel-Vahan, a teenager in a Baghdad orphanage in 1919, decides to go back and find his paternal home in Khaskal. Accompanied by his eldest, surviving sister Srbuhi and her husband, they start their odyssey travelling through deserts, hills and valleys, pastures and sea (reversing their march of death), finally reaching their destination.

They reclaim their paternal home, albeit derelict and completely depleted of household furniture and all. After a few months of sustained and determined efforts of survival, their mansion too breathes new life. But the atmosphere of fear, rekindled by ultra nationalism, poisons the life of those groups who dared outlive the Genocide. To continue surviving, my father and his sister’s family had to leave their paternal home yet again, but not before procuring a photo-memento (taken by a soldier of the retreating Greek armies), of their beloved mansion—a “miraculous” feat, indeed.

During the summer of 1963, Israel-Vahan Pilikian, then 60 and a father of a large family with five children residing in Beirut, Lebanon, revisited his birthplace in Khaskal. No traces of the house were found. There the locals told him, that ‘that impressive mansion on the hill’ was finally burned down during the nationalist upheavals…

Based on that “miraculous” photograph of 1920, I sketched with pastel-crayons, on January 13th, 1957, an enlarged (cm. 61.5 x 46.5) picture of our ancestral ‘mansion on the hill’ in Khaskal.

The Armenian inhabitants of the region Agn, in Historical Armenia (Egin, now Kemaliye, in Turkey), were mostly descendants of Ani, the ancient capital of Armenia captured by the Mongol invaders in 1236.

The Aniites having become Agnites for three centuries were uprooted anew, this time by the Ottoman Turks, during the 16th century. Hence the name Khaskal of the original village in Agn, was given by the Armenian immigrants from Agn to their new settlement in Izmit-Nicomedia, neighbouring Constantinople in Anatolia.

The new Khaskal, meaning “good-fields”, proved worthy of its name. It soon became the ‘Paradise’ of the region, especially for the pilgrims of the celebrated Armenian Monastery of Armash. (S. M. Dzotsikian, Arevmdahay Ashkharh [Western-Armenian World], New York: Dzotsikian Jubilee Committee, 1947, p.484). Centuries passed, then most of the Khaskalites, those great grand-grand-grand children of Aniite Agnites, were uprooted yet again, this time to become victims of the ‘first final solution’ of the 20th century—The Genocide of the Armenians, perpetrated by the proto-Nazi government of the Young Turks.

The only belonging our large Pilikian family had of my parent’s ancestral material positions was that photograph of our ancestral mansion. During many upheavals in the Middle East, culminating in the Lebanese civil war, our large Pilikian family was already fragmented in various parts of the world; Europe – my sister Margaret and her family in Paris; UK – my younger brother Hovhanness and his family in London; Canada – my twin sister Arsineh and children in Montreal (having lost her husband during the Lebanese civil war), while my eldest sister Mary and her family in Toronto. Mary was already a prominent pharmacist in Beirut, while my brother Hovhanness had become a prominent theatre director in London.

After studying and residing in Italy for ca ten years, I was in USA as a Fulbright scholar, while the Lebanese civil war was on, and the Vietnam war seemed to drag the USA into its own civil war yet again. My father and mother were still in Beirut, helped by my twin sister before she too left to join her son and daughter in Montreal.

I was already in London in early 80’s when my parents left Beirut for good and came to live with us, brothers, in London. The havoc of emigration caused enormous losses, not the least of which was my father’s treasured memento – the visual, photographic image of our ‘ancestral mansion on the hill’. Notwithstanding all, my copies of Annunciation and the Mansion on the Hill, miraculously survived the traumatic conditions in all the fields of existence during the fifteen years of the Lebanese civil war that caused ca 150 thousand lost lives and all.

My reproductions of Annunciation and Mansion on the Hill worked ‘magic’ in late 1950s. They convinced my parents that Italy is where I should be, especially when I also performed as a solo tenor with Maestro H. Berberian’s orchestra and chorus, at UNESCO Hall, celebrating the 100th Anniversary of AGBU (Armenian General Benevolent Union, founded in 1906). My parents’ conviction had the enthusiastic support by the Headmaster of the Department of Architectural Engineering of the AUB, Dr Ghoseyn, who was, alas, brutally assassinated during the civil war in Lebanon.

I was in Rome in the summer of 1957. As a full teenager and beyond, I opened my eyes, mind and soul in Rome, in various Fine Art and Music Academies, while continuing my studies at the Architectural Faculty, University of Rome.

When the National Gallery had among others Murillo paintings exhibition in mid 80’s, I was hoping to see the original of the Annunciation (1679-1689). But there I found many other paintings closely related with it. I was happy that my copy was not so alien to the original ‘atmosphere’ I witnessed at the exhibition.

But then, my own artistic style was already formed in early 60’s. My Amore Eterno is a good example of that.

——————–

Here is a concise ‘presentation’ for my painting AGNUS DEI, contrasting it with another one – AMORE ETERNO (both attached).

AGNUS DEI, painted in Milan in 1965, to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of April 24.

AMORE ETERNO, painted in Rome in 1960…(International Gentes Ars = People’s Art Prize 1961, graced the cover of the Vatican’s biweekly,Crociata (no. 23)).

Man’s Inhumanity to Man is like crucifying the childhood of humanity.

–In AGNUS DEI, the right hand finger of the child — already in a mature state – is poised in a pointing position towards the onlooker.

–Mother’s embracing arms are pulled downward, lacking the joyful upward strength when embracing her child in happiness, as in AMORE ETERNO).

–The background scenery is obviously Ararat.

–The entire shape of the cross is like an axe, visually bisecting the anguished mother, rendering her as a majestic heart.

–The depleted sunflower has a bisected moon facing it… etc.

Indeed, AGNUS DEI is the landscape of the crucified childhood of humanity. Disturbing for sure, as it should really be…

In contrast, AMORE ETERNO is what healthy humanism is all about.

=========================================================