The Armenian Diaspora Project conducts research survey of public opinion in Armenian diaspora communities to inform the public, scholars, policy-makers and community leaders about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the Armenian world in the 21st century.

Led by a team of academics, researchers and experts, the Armenian Diaspora Survey (ADS) aims to provide a snapshot of the contemporary Diaspora. The project fills a critical gap in the knowledge of the Diaspora and provides evidence-based understanding of the multilayered and diverse aspects of diasporic life.

ADS is funded by the Armenian Communities Department of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and carried out under the auspices of the Armenian Institute in London.

Over 1000 Armenians in four cities in the Diaspora took part in this first ever survey, which was led by a team of academics, researchers and experts. In May and June 2018 four teams conducted the survey and interviews in Boston, Cairo, Marseille and Pasadena. These cities were chosen to provide variety for the initial phase, as well as for their community history and characteristics.

Some initial findings stand out in the first stage of the research (entire report here).

The overwhelming majority of the respondents consider the continuation of the Armenian diaspora as important and meaningful space—94% marked as “fairly” to “very” important. Along these lines, 84% of respondents felt it was important to help diaspora communities in the Middle East. This is significant as traditionally the Genocide and the Republic of Armenia have been the focus of funding, study or discourse in the Diaspora. The respondents showed interest in all of these, but considered the diaspora equally important. Armenia is “fairly” and “very” important to 90% of respondents and 75% have visited the country at least once, while 93% intend to visit.

Respondents said that Armenian language, history and religion were important to themselves and to Armenian identity generally—but variations appeared between the cities and further questions revealed broad variations in practice.

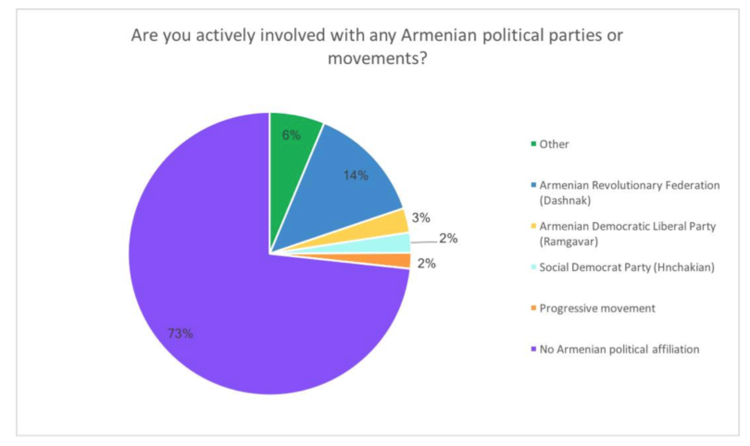

Even as ADS respondents in the four cities seem to be more active than perhaps a broader population of Armenians, 73% claimed no active affiliation with any Armenian political organization. However a majority said they were active in other Armenian organizations such as the AGBU, Hamazkain and others.

Predictably, Christianity is considered an important part of Armenian identity—for Apostolic, Evangelical and Catholic respondents across the four communities. While only 14-16% attended church weekly or monthly, 70% felt it is important to be married in an Armenian church. Some 43% of respondents felt that women should be ordained in Armenian churches, while 30% had no opinion on the matter.

Diaspora survey provides a snapshot of Armenians in the 21st century

March 15, 2019

LONDON—Over 1000 Armenians in four cities in the Diaspora took part in a first ever survey led by a team of academics, researchers and experts. This pilot phase of an ongoing larger project aims to provide a snapshot of the contemporary Diaspora.

The Armenian Diaspora Survey (ADS) is a new initiative launched and funded by the Armenian Communities Department of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and carried out under the auspices of the Armenian Institute in London.

“We have initiated this study to fill a critical gap in our knowledge of the Diaspora, to have evidence-based understanding of the multilayered and diverse aspects of diasporic life in our times,” said Dr. Razmik Panossian, Director of Gulbenkian Foundation’s Armenian Communities Department.

In May and June 2018 four teams conducted the survey and interviews in Boston, Cairo, Marseille and Pasadena. These cities were chosen to provide variety for the initial phase, as well as for their community history and characteristics. A set of other cities are in the process of selection for survey this year.

“We asked people about their thoughts on identity and related issues of belonging as Armenians and as citizens of different states,” explained Dr. Susan Pattie, who led the pilot project. An international advisory committee, a dedicated team and 12 field work researchers were involved in the project, which took about 18 months to develop the methodology, research tools, fieldwork preparations, survey administration and data processing.

For institutional and community leaders in the Diaspora, as well as policy-makers in Armenia, ADS provides valuable research-based information as to what the issues and thinking in the Armenian communities are today and how to serve their needs.

The data and the knowledge gained from the survey will be available to scholars as a resource for further research.

Some initial findings stand out in the first stage of the research. These are only preliminary results from the pilot phase of the survey in four cities.

The overwhelming majority of the respondents consider the continuation of the Armenian diaspora as important and meaningful space—94% marked as “fairly” to “very” important. Along these lines, 84% of respondents felt it was important to help diaspora communities in the Middle East. This is significant as traditionally the Genocide and the Republic of Armenia have been the focus of funding, study or discourse in the Diaspora. The respondents showed interest in all of these, but considered the diaspora equally important. Armenia is “fairly” and “very” important to 90% of respondents and 75% have visited the country at least once, while 93% intend to visit.

Respondents said that Armenian language, history and religion were important to themselves and to Armenian identity generally—but variations appeared between the cities and further questions revealed broad variations in practice.

Even as ADS respondents in the four cities seem to be more active than perhaps a broader population of Armenians, 73% claimed no active affiliation with any Armenian political organization. However a majority said they were active in other Armenian organizations such as the AGBU, Hamazkain and others.

Predictably, Christianity is considered an important part of Armenian identity—for Apostolic, Evangelical and Catholic respondents across the four communities. While only 14-16% attended church weekly or monthly, 70% felt it is important to be married in an Armenian church. Some 43% of respondents felt that women should be ordained in Armenian churches, while 30% had no opinion on the matter.

“Armenians in each community expressed the need to be listened to. They welcomed the opportunity to discuss their experiences, expectations and hopes as individuals and as Armenians,” explained Dr. Pattie. Many ways of being Armenian were reflected in the responses and for those who took part. “Expressing this diversity within a common bond was most important,” Dr. Pattie added.

The survey will continue in 2019 with a new set of selected cities. In the meantime, the results of the pilot survey are being studies and analyzed, which will be shared with the public and will be made easily accessible in the coming months. Further details are on ADS website: www.armeniandiasporasurvey.com.

Diaspora Politics

Leon Aslanov

Aside from institutions such as the Church and schools, political parties have generally represented one of the key institutional actors that aim to “preserve Armenianness” (hayabahbanum) in the Armenian diaspora. Their roles have mainly been limited to preserving communities and the Armenian identity through social and cultural endeavours. Their political activities have largely been restricted to genocide recognition, apart from in Lebanon, where the parties are involved in national politics. The three main parties in the Diaspora continue to be the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF – Dashnak), the Social Democrat Party (SDHP – Hnchak), and the Armenian Democratic Liberal Party (ADLP – Ramgavar). One simple question in the ADS survey asked respondents what political affiliations they had to Armenian political parties or movements. The overall results from the 4 communities in the study came out as follows:

A very low rate of Armenian political affiliation indeed. And this low rate was reflected across all 4 cities. The rate of “No Armenian political affiliation” was higher in the Western locations (US and France), as it hovered around the 75% mark for Boston, Pasadena and Marseille. Cairo, the smallest and only Middle Eastern community in the survey, was home to a stronger political party presence as it recorded a rate of 63.6% for “No Armenian political affiliation” and registered a higher rate of political affiliation to all 3 political parties than in the other cities.

The ARF, unsurprisingly, came out on top in all of the communities and it recorded a significant presence in Cairo with a 19.2% rate of political affiliation. Some respondents commented that although they do not officially belong to the ARF, many of them are former members with continuing sympathies or have a family legacy attached to the party. The continuing attachment to the ARF despite the lack of official affiliation represents the socio-cultural nature of the party in that its traditions and organisational structure have left behind a legacy that is not outwardly political but has formed bonds between those with connections, however distant, to the party. One respondent from France described themselves as “”dachnakoïde” (de culture dachnag non miltante)”.

Interestingly, when respondents were asked about what activities were needed in their communities, political activism (e.g. Genocide recognition or lobbying for aid to Armenia) was deemed relatively important in the French context of Marseille, but it scored rather low in the American context. Nevertheless, this sort of diaspora political activism was not considered anywhere near a top priority as was language, education and cultural activities.

The term “progressive movement” was added to the list of the abovementioned question despite the lack of a concrete political party to represent it. There is also no cohesive “progressive movement” in the Armenian diaspora. However there are Armenians who define themselves as “progressive” and we felt it important to find out whether anybody would affiliate themselves with such a movement. In the end, only Boston saw a rate worth mentioning, with 4.3% saying they belong to the “progressive movement”, while the term scored 1% or less in the other locations. Another question was asked in the survey about respondents’ general political orientations (Conservative, Liberal, Progressive etc.) in which the score for “progressive” self-identification was relatively much higher than the score for “progressive movement” in the question discussed here. This difference will be discussed in more detail in a future blog post.

With the influx of immigrants from the Republic of Armenia into diaspora communities, it is likely that the relevance of Armenian diaspora political parties will continue to diminish. Immigrants from Armenia are detached from the historical importance and dynamics of the traditional political parties in the diaspora and so are unlikely to be involved with them. The only party to exist both in the diaspora and the Republic is the ARF, however their following in Armenia is minute and, apart from a common nationalist ideology, the “homeland” and “diaspora” versions share little with one another on a socio-cultural level. The other two parties in the diaspora seem to be breathing their final breaths…

Introduction to Initial Results of the Pilot Project

Susan Pattie, Leader, Pilot Project, Armenian Diaspora Survey.

When our teams visited the 4 cities of Boston, Cairo, Marseille and Pasadena, one question kept reappearing in each place. What is this FOR? Why are you doing a survey?

We, the ADS team, are driven by curiosity and long-term interest, as well as a certain love of the diaspora as our home – but over these 18 months of the Pilot Project, we have shifted from taking our aims for granted to a clearer look at the motivations behind this study.

The Armenian Diaspora Survey aims to gather clear and tangible information about the contemporary diaspora. Asking Armenians about their thoughts about Armenian identity and related issues of belonging as Armenians and as citizens of different states, we seek to create a resource that gives a voice to those taking part and which forms a snapshot of the diaspora today. This is the first time that such a study has been done on this scale with extensive team-work and expertise behind it. The data and its analysis can be used by scholars for better understanding and as a foundation for further research. It can also be used by leaders of the diaspora and of the Republic of Armenia for practical information about how to effectively serve Armenian communities.

What have we learned from the Pilot Project of the ADS? With substantial results of over 800 questionnaires and 200 interviews, there is much to consider. Given the many million Armenians in the diaspora, this is a small percentage of those whom we hope will take part over time but the Pilot has helped us to formulate questions, re-formulate, and listen to people’s thoughts. We will present and discuss what we’ve found so far in regular blogs and articles but here are a few thoughts to begin with.

The continuation of the Armenian diaspora as an important and meaningful space was marked as “fairly” to “very” important by 94% of respondents, making this the most “unanimous” of answers across the communities. In line with this, 84% of respondents felt it was important to help diaspora communities in the Middle East. This is significant as so often the focus of funding, of study, of general attention seems to be either the Genocide or the Republic of Armenia. The respondents showed that they are interested in all of these and that the diaspora is equally important. The Republic of Armenia is “fairly” to “very” important to 90% of respondents and 75% have visited at least once. 93% intend to visit (again for some).

Unsurprisingly, respondents said that Armenian language, history and religion were important to themselves and to Armenian identity generally – but variations appeared between the cities and further questions revealed broad variations in practice. Although our set of respondents in the 4 cities seem to be more active than perhaps a broader population of Armenians, 73% claimed no active affiliation with any Armenian political organization. However a majority said they were active in other Armenian organizations such as the AGBU or Hamazkaine or others. Christianity was believed to be an important part of Armenian identity (including Apostolic, Evangelical and Catholic respondents across the 4 communities) but 14-16% attended church weekly or monthly while 70% felt it is important to be married in an Armenian church. Some 43% of respondents felt that women should be ordained in Armenian churches while 30% had no opinion. These topics and others will be discussed and contextualized in future blogs.

Overwhelmingly, Armenians in each community told us what our purpose was – to listen to them, to give them an opportunity to talk about their past and future as individuals and as Armenians. Many ways of being Armenian were reflected in the responses and for those who took part, expressing this diversity within a common bond was most important. Of course, there were also many similar responses but among the open-ended questions, responses ranged greatly.

The Survey will continue in 2019, visiting new cities. Meanwhile, we are studying and analyzing the results of the 2018 Pilot, learning how to improve our methods. Over the next weeks we will be posting some interesting results from the questionnaires, raising questions about the different shapes that “belonging” takes for each of us. Stay tuned!

The Survey is funded by the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon whose mission includes supporting research and education. It is administered by the Armenian Institute, London.

Armenian diaspora studies takes a new turn

Leon Aslanov

As we began the Armenian Diaspora Survey, one aim was to uncover as much of the work done about the Armenian diaspora as possible. Material written about the Armenia diaspora is rich and diverse, but scattered all across the globe. Up until then, there was no single database of such works to which academics, students, and interested individuals could refer. And so began my endeavor to plough through university websites and academic databases, and to get in touch with various individuals in the field of Armenian studies, in order to begin forming the first collection of works about the Armenian diaspora in one place. These include academic articles, books, and dissertations (Master’s and PhD). All the works are available in PDF format. In this way we hope to make these works more accessible and useful for our own study of the diaspora but also so they can be used more easily by others as a foundation for their own work, rather than reinventing the wheel.

My knowledge of various languages finally came to be of practical use. My initial task was to find material in English, French, Turkish and Eastern/Western Armenian, moving on to Russian later on. Much of the English and French-language material was easily accessible through searches on global academic websites and university databases (despite some of the obstacles faced when encountering the protectionism of certain universities). I noticed that the English-language works touched upon a diverse range of Armenian communities, from both within and outside of the Anglophone world. The French-language research papers, in contrast, were almost entirely focused on exploring the Armenian communities of France. The resplendent diversity of the English-language research was complemented by the rich and in-depth research related to the history, culture and identities of Armenians in France.

I found the differences in approach between Armenian-American and Armenian-French researchers interesting. I came across several pieces of research from the US that employed more rigorous social science methods (quantitative and qualitative) to investigate Armenian communities there, particularly from the West Coast. The French papers, on the other hand, were more descriptive and analytical in nature; some almost read like a novel narrating the story of the Armenian communities in France.

There was also a surprising number of works that focused solely on the issue of acculturative stress among Armenians in the US. These works merged psychology and the social sciences to investigate the nature of Armenian integration into American society, and the psychological stress caused by cultural and inter-generational differences. This was a topic that seemed to be popular in the US, but was rarely touched upon in any of the other countries.

Moving on to Turkish. The Armenians of Turkey could hardly be called a diasporic group, however, they reside in a country where they exist as a small minority, and so issues regarding identity, integration and assimilation are highly pertinent, just like in Armenian communities across the diaspora. My search in Turkish brought up an astonishing number of research papers (over 65) conducted by Armenians, Turks and Kurds in Turkey. The majority of these works focused on local Armenians across Turkey, migrants who had moved from Armenia to Turkey, and also the so-called “Islamised” Armenians. Despite a number of evident obstacles imposed by universities and the Turkish state on writing freely about Armenians in Turkey (especially when it comes to mentioning genocide and the memory of genocide), the papers in Turkish provide an extremely valuable insight into what researchers in Turkey regard as important when it comes to Armenians. Memory and identity were topics that continuously came up in my search. The fact that so many students in Turkey who were not Armenians (evident from their names[1]) was in itself revealing and a significant discovery.

As for the Armenian-language works, these can be largely divided into three groups: Eastern Armenian papers composed by students at universities in Armenia, Eastern Armenian books written by researchers funded by the Ministry of Diaspora, or Western Armenian works were mostly written by students from Lebanon, especially from the Haigazian University.

Finally, the Russian-language works, naturally, explored Armenian communities in the post-Soviet space, a somewhat strange category of “Armenian diaspora” that is able to continue to feel at home away from home, in a kind of “Soviet continuum”.

This collection gives researchers access to an abundance of material that is especially conducive to comparative research of Armenian diaspora communities. The variety in the research is not only connected to the focuses on different Armenian localities, but it also consists of a variety of academic, social, and personal perspectives from which these works were composed.

I hope that this bibliography will continue to grow and incorporate more languages, more communities, and more perspectives. I believe that this collection will herald a new development in Armenian and diaspora studies. The opportunities for comparison and analysis have now been expanded.

[1] Armenians in Turkey sometimes have Turkified surnames (although not always), but they normally hold on to “Christian”, “European”, or Armenian first names (e.g. Monika or Sevan). Names belonging to ethnic Turks are often easily identifiable if the first name relates to Islamic tradition (e.g. Zeynep or Mustafa) or if both first name and surname are of Turkish origin.

(Download 2018 Pilot Survey report)

https://www.armeniandiasporasurvey.com/newsandviews