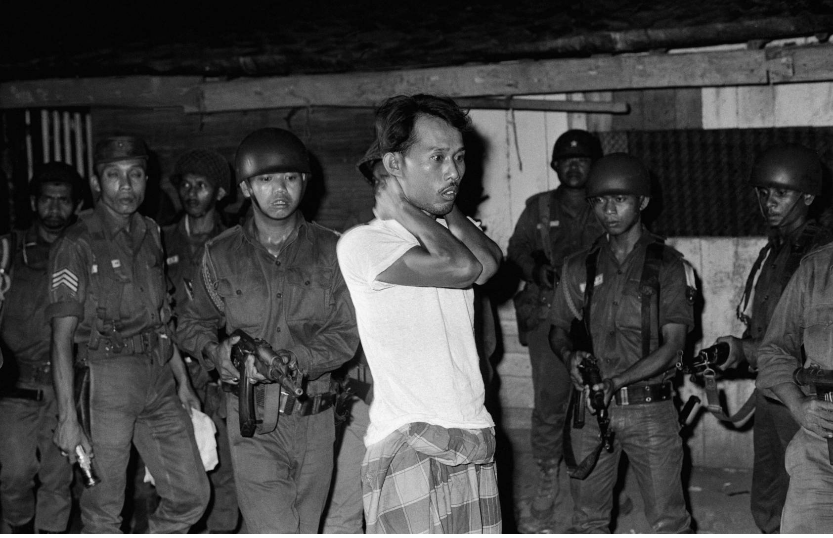

An alleged communist is questioned under gunpoint by Indonesian soldiers in 1965. (University of Melbourne)

The massacre of the Indonesian left in 1965–66, backed by Washington, was one of the great crimes of the twentieth century. A new generation of scholars has uncovered its long-suppressed history of slaughter of up to a million people in the name of anti-communism.

Review of Buried Histories: The Anticommunist Massacres of 1965–1966 in Indonesia, by John Roosa (University of Wisconsin Press, 2020).

On the night of September 30, 1965, a bungled coup d’état resulted in the deaths of a handful of Indonesian generals, a lieutenant, and the five-year-old daughter of one general who escaped the kidnapping. Within days, a relatively unknown military figure, Suharto, had jumped the chain of command. Suharto blamed the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), the largest communist party outside of the Soviet Union and the People’s Republic of China, for the murders. And he promised revenge.

This set in motion a mysterious and often perplexing series of events that led to the downfall of Indonesia’s founding president, Sukarno — an anti-imperialist who had sought to forge national unity by combining the forces of nationalism, religion, and communism — and the rise of the authoritarian General Suharto’s New Order (1966–1998), a period of far-right military dictatorship, massive corruption, and unbridled foreign investment. Suharto both prefigured and outlasted his Chilean analog, Augusto Pinochet.

The circle of officers around Suharto immediately incited public opinion against the PKI. Claiming there was a massive conspiracy they called Gestapu or G30S/PKI (short for “September 30th Movement/PKI”), they warned of an imminent threat of a nationwide Communist uprising. On orders from Jakarta, regional commanders began campaigns of arrest, torture, and execution.

We don’t have exact numbers, but the army and its allies killed somewhere between five hundred thousand and a million people in the space of a year, with an equivalent number sent to brutal prisons throughout the nation’s sprawling archipelago, the most infamous of which was Buru Island. Prisoners worked as slave laborers for years. After release, they were subject to official repression and treated as social pariahs. Even the children of former prisoners faced serious discrimination.

The PKI was the alleged target of this bloody purge, but it also engulfed many other leftists, including feminists, labor organizers, and artists. Because the killers ran the state for decades, a generation of Indonesians ingested a steady stream of lurid propaganda that falsely claimed the PKI had been planning its own campaign of mass murder. Despite the fall of Suharto and the restoration of democracy, this lie remains the official narrative of the Indonesian state. As shown by recent anti-communist demonstrations in Jakarta and book raids in provincial cities, red-baiting remains a powerful force in contemporary Indonesian politics.

International Silence

While these events made international headlines in 1965, they were quickly forgotten in the West. Why was “one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century” — as a 1968 CIA report described it — swept under the rug so quickly? In 1973, a secret CIA document expressed relief with the dramatic change of guard at the top:

Sukarno couched his leadership drive in revolutionary rhetoric and believed Indonesia should dominate its neighbors; Suharto talks of pragmatic solutions to the problems of the region and sees Jakarta as first among equals.

Suharto’s vocal anti-communism and his willingness to serve US Cold War interests encouraged steady streams of military aid and foreign capital. Washington’s reluctance to condemn the crimes of the New Order was consistently bipartisan.

After initially celebrating the fall of Sukarno and the neutralization of the PKI, with some throat-clearing about its regrettably bloody character, the Western press had little to say about Indonesia. Once Suharto had eliminated the PKI, the war in Vietnam moved to center stage. After 1975, Communist atrocities, whether real or imagined, dominated coverage of Southeast Asia.

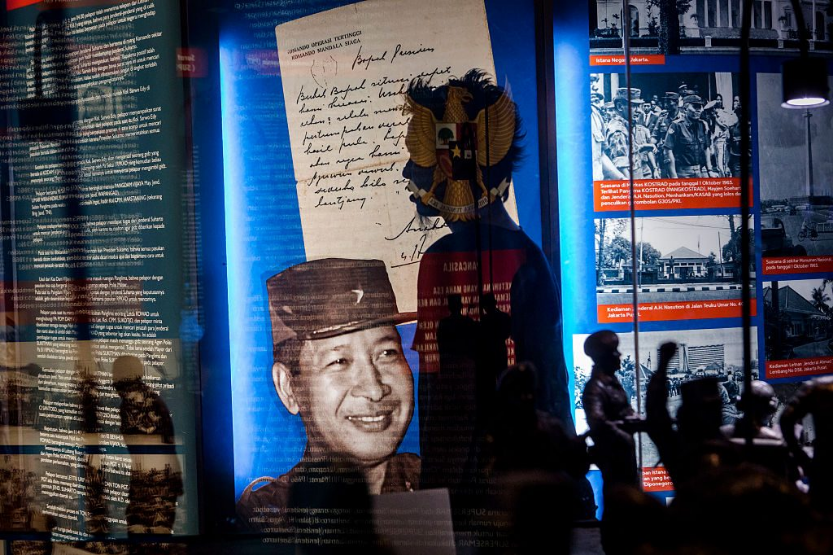

A visitor walks past a picture of Suharto, the former Indonesian dictator, at Suharto museum on May 06, 2016 in Yogyakarta. (Ulet Ifansasti / Getty Images)

Only a few journalists covered the Indonesian beat. Books such as John Hughes’s 1967 Indonesian Upheaval regurgitated the Indonesian Army’s self-serving narrative. Hughes trafficked in orientalist stereotypes of Javanese peasants gone amok in a primordial orgy of violence and devout Balinese Hindus calmly marching to meet their killers. Richard Lloyd Parry’s 2006 book, In the Time of Madness: Indonesia on the Edge of Chaos, followed in his footsteps.

In the film Manufacturing Consent, Noam Chomsky noted that the Western press failed to cover right-wing, anti-communist violence as carefully as human rights violations in Communist states. He contrasted the extensive New York Times coverage of the Khmer Rouge regime (1975–78) with the scant attention the paper paid toward Suharto’s genocidal invasion and occupation of East Timor (1975–1999).

For decades, political activists and scholars were frustrated by widespread indifference to the wrongful detention, brutal torture, and mass murder of hundreds of thousands of Indonesians. Amnesty International and TAPOL, joined by the East Timor Action Network in 1991, engaged in campaigns to expose the New Order’s human rights violations. Yet their efforts often seemed futile, as corporate media paid scant attention to the situation.

Academics were often hesitant to speak out. Benedict Anderson and Ruth McVey authored a secret report critical of the regime in 1966, and George McT. Kahin had Cornell University publish the so-called “Cornell Paper” in 1971; all of these Indonesian specialists subsequently found themselves banned from entering the country. This had a chilling effect on other scholars critical of the regime.

Serious research on the subject was next to impossible in Suharto’s police state. Many academics chose self-censorship in the hopes of securing highly prized research visas. Before my first trip to Indonesia as a graduate student in 1990, faculty warned me not to discuss 1965.

A Suddenly Robust Historiography

The Southeast Asian economic crisis of the late 1990s hit Indonesia especially hard, and a people-power revolution overthrew Suharto in 1998. Suddenly, the rules changed. Political prisoners were released, and interim president B. J. Habibie allowed East Timor to hold a referendum on independence. Habibie’s elected successor, Abdurrahman Wahid (known as Gus Dur), acknowledged the complicity of Islamic organizations in the mass killings of 1965–66 and discussed the need for reconciliation.

Scholars and activists seized the moment. My friend Bonnie Triyana, then an undergraduate, would go on to found the country’s first popular history magazine, Historia. He talked his way into a provincial military archive and gained access to dossiers detailing the destruction of a central Javanese village. John Roosa, a recently minted American PhD who had specialized in South Asian history in graduate school, had a family member imprisoned under Suharto. Using connections made while visiting the prison and contacts in the local activist community, he began to interview former political prisoners.

Some of this work formed the basis of Roosa’s book, Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup d’État in Indonesia, the definitive political history of the event that set the Indonesian genocide in motion. Published in 2006, Pretext for Mass Murder signaled a sea change in what was possible in 1965 studies. Now an associate professor of history at the University of British Columbia, Roosa has written a sequel to Pretext for Mass Murder.

The product of over two decades of work, Roosa’s Buried Histories: The Anticommunist Massacres of 1965–1966 in Indonesia is a carefully crafted study of these events. The book sheds light on the previously hidden mechanics of mass murder and dispels a number of myths about this dark moment in Indonesian history. Based on scores of interviews as well as archival research, Buried Histories is a welcome addition to the growing scholarly work on what some have termed a political genocide.

Sukar, 83, a villager who witnessed Indonesia’s anti-communist massacre, stands next to the tombstone which was installed by activists and families of victims on the site where it is believed victims were buried inside the teak forest in Plumbon village on May 03, 2016 in Semarang, Central Java, Indonesia. (Ulet Ifansasti / Getty Images)

Readers of Jacobin may know that there have been a series of recent books on the events of 1965–66, many of them reviewed here. If historians such as Geoffrey Robinson, Jess Melvin, and Annie Pohlman and journalists like Vincent Bevins have all made significant contributions to the subject, one may ask what another book can offer. Fortunately, the answer is quite a lot.

Buried Histories is a book in two parts. The powerfully written introduction manages to both humanize this horrific history and present an overview of the events and a summation of the historiography. Chapters 1–4 explain issues that impacted Indonesia as a whole, while chapters 4–7 offer case studies of specific regions.

While focused on distinct local contexts, each chapter offers a powerful and insightful argument that is relevant to Indonesia’s national history as a whole. The conclusion concisely lists the groups most responsible for the murders: high army officials, regional commanders, and civilian militias. A final section describes the difficulties and dangers of honestly discussing this history in contemporary Indonesia.

A Gramscian Rivalry

Roosa starts with a discussion of the struggle between the PKI and the army during the period of Sukarno’s Guided Democracy (1957–1965). Noting that under the leadership of D. N. Aidit, the PKI abandoned a strategy based on armed insurrection for one geared toward electoral contests, Roosa uses Antonio Gramsci’s theory of hegemony to describe how Aidit, after the suspension of democracy under Sukarno, built up the party’s influence by mobilizing mass organizations of fellow travelers.

SOBSI organized the union movement, LEKRA brought artists together, and the BTI helped peasants implement land reform. The party was also closely allied with Gerwani, possibly the world’s largest women’s movement in the early 1960s, although it was not PKI-controlled.

Mirroring the PKI’s Gramscian strategy, the army expanded its power throughout Indonesia under the guise of the Territorial Command. This organizational structure allowed the army to place its officers in provincial government offices, giving the military significant influence, if not outright control, of the administrative bureaucracy, as well as excellent sources of intelligence.

While both the PKI and the army were successful in extending their influence throughout the sprawling archipelago, only the military had access to weapons. When the conflict erupted in October 1965, it was very easy for the army to seize control of the state and move against its unarmed and unsuspecting opponents. Roosa indicates that there is substantial evidence that the US-trained officers were waiting for the pretext to attack the PKI, a theme that Vincent Bevins stresses in The Jakarta Method.

Mental Operations

Roosa’s next two chapters explain the army’s use of propaganda and torture. Engaging in what the generals called “Mental Operations,” immediately after the failed coup, army-controlled newspapers and radio blamed the PKI for the murders and warned of a larger campaign of bloodshed. According to this propaganda campaign, likely preplanned and certainly orchestrated, the army had to crush the PKI in order to stop the party from engaging in mass slaughter.

This kill-or-be-killed argument was a lie. The press falsely and illogically claimed that the PKI was stockpiling secret weapons and secretly digging mass graves for its intended victims. Spreading false but morbidly fascinating rumors of crazed Gerwani members allegedly sexually mutilating the generals, the army used misogyny to mobilize anti-PKI sentiment.

Once the mass arrests had begun, the army turned to the systemic use of torture. On first glance, the routine use of torture seems merely sadistic and of no practical purpose, but Roosa persuasively argues that it served to promote the lies of the propaganda machine. Prisoners were tortured until they gave absurd confessions.

Following the work of Annie Pohlman and Saskia Wieringa, Roosa shows that women were subjected to widespread rape and other forms of sexual violence. Despite their ignorance of what had happened in Aidit’s inner circle of PKI leaders, rank-and-file party members, union members, and hundreds of thousands of others caught up in the army’s dragnet were tortured until they confessed to participation in a massive conspiracy, often implicating other innocents.

(Ulet Ifansasti / Getty Images)

While obviously false, these statements could be used as proof to justify the army’s campaign of violence. Once a person had signed the confession, it became a legal fact in the eyes of the state, justifying their arrest and rationalizing the search for more members of the so-called G30S/PKI conspiracy. Torture essentially willed the conspiracy theories of Mental Operations into existence.

Roosa’s argument sheds light on the similar use of torture by the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia. The equally absurd confessions extracted in Phnom Penh’s Tuol Sleng prison were a way for the Pol Pot regime to rationalize its actions and confirm its ideology. While at opposite ends of Cold War Southeast Asia’s political spectrum, Cambodian Communists and Indonesian anti-communists both instrumentalized violence to make their paranoid fantasies a bureaucratic reality.

Deadly Surprises

The second section of Buried Histories looks at the destruction of the PKI in Surakarta, disappearances in Bali, the Kapal massacre in Bali, and the army’s attack on unionized oil workers in Sumatra. In each case, Roosa dispels John Hughes’s orientalist myth that attributes the killing to hysterical mobs of anti-communist patriots, enraged Muslims, and fatalistic Hindus. Instead, like Robinson and Melvin, he demonstrates that the army leadership in Jakarta carefully orchestrated the violence, which was implemented on the ground by regional officers who often relied upon organized crime and anti-communist mass organizations, such as the Muslim Nahdlatul Ulama, for muscle.

The army’s success was based on the well-planned deployment of military force against unprepared civilians. With plans having been put into motion well before PKI members had any notion that they were in danger, resistance in such a situation was next to impossible. The national campaign of mass murder lasted for roughly six months. Beginning in Aceh in the far west and then moving east through Sumatra, Java, and onto Bali, the massacres were a series of surprise attacks on a legal civilian party and its allied organizations. Roosa shows how the PKI members in Central Java and Bali willingly went to police stations when summoned, having no idea of the horrors that awaited them.

By combining nationwide chapters with regional case studies, Buried Histories shows us both the forest and the trees. Throughout the text, Roosa never loses sight of the horrors inflicted upon individuals who did not know they were in danger. In the end of the book, he addresses the various attempts to acknowledge these crimes and the ongoing backlash against a moral and just assessment of this dark history.

In this age of rising authoritarianism and polarizing political violence, Buried Histories is essential reading. After a year in which unidentified federal agents seized American citizens on the streets of Portland, we would do well to study Indonesia 1965 as an object lesson.

About the Author

Michael G. Vann is a professor of history at Sacramento State University and the author, with Liz Clarke, of The Great Hanoi Rat Hunt: Empire, Disease, and Modernity in French Colonial Vietnam.

https://jacobinmag.com/2021/01/indonesia-anti-communist-mass-murder-genocide