By Sudarsan Raghavan, Published May 26, 2022

DRUZHKIVKA, Ukraine — Stuck in their trenches, the Ukrainian volunteers lived off a potato per day as Russian forces pounded them with artillery and Grad rockets on a key eastern front line. Outnumbered, untrained and clutching only light weapons, the men prayed for the barrage to end — and for their own tanks to stop targeting the Russians.

“They [Russians] already know where we are, and when the Ukrainian tank shoots from our side it gives away our position,” said Serhi Lapko, their company commander, recalling the recent battle. “And they start firing back with everything — Grads, mortars.

“And you just pray to survive.”

Ukrainian leaders have projected and nurtured a public image of military invulnerability — of their volunteer and professional forces triumphantly standing up to the Russian onslaught. Videos of assaults on Russian tanks or positions are posted daily on social media. Artists are creating patriotic posters, billboards and T-shirts. The postal service even released stamps commemorating the sinking of a Russian warship in the Black Sea.

Ukrainian forces have succeeded in thwarting Russian efforts to seize Kyiv and Kharkiv and have scored battlefield victories in the east. But the experience of Lapko and his group of volunteers offers a rare and more realistic portrait of the conflict and Ukraine’s struggle to halt the Russian advance in parts of Donbas. Ukraine, like Russia, has provided scant information about deaths, injuries or losses of military equipment. But after three months of war, this company of 120 men is down to 54 because of deaths, injuries and desertions.

The volunteers were civilians before Russia invaded on Feb. 24, and they never expected to be dispatched to one of the most dangerous front lines in eastern Ukraine. They quickly found themselves in the crosshairs of war, feeling abandoned by their military superiors and struggling to survive.

“Our command takes no responsibility,” Lapko said. “They only take credit for our achievements. They give us no support.”

When they could take it no longer, Lapko and his top lieutenant, Vitaliy Khrus, retreated with members of their company this week to a hotel away from the front. There, both men spoke to The Washington Post on the record, knowing they could face a court-martial and time in military prison.

“If I speak for myself, I’m not a battlefield commander,” he added. “But the guys will stand by me, and I will stand by them till the end.”

The volunteers’ battalion commander, Ihor Kisileichuk, did not respond to calls or written questions from The Post in time for publication, but he sent a terse message late Thursday saying: “Without this commander, the unit protects our land,” in an apparent reference to Lapko. A Ukrainian military spokesman declined immediate comment, saying it would take “days” to provide a response.

“War breaks people down,” said Serhiy Haidai, head of the regional war administration in Luhansk province, acknowledging many volunteers were not properly trained because Ukrainian authorities did not expect Russia to invade. But he maintained that all soldiers are taken care of: “They have enough medical supplies and food. The only thing is there are people that aren’t ready to fight.”

But Lapko and Khrus’s concerns were echoed recently by a platoon of the 115th Brigade 3rd Battalion, based nearby in the besieged city of Severodonetsk. In a video uploaded to Telegram on May 24, and confirmed as authentic by an aide to Haidai, volunteers said they will no longer fight because they lacked proper weapons, rear support and military leadership.

“We are being sent to certain death,” said a volunteer, reading from a prepared script, adding that a similar video was filmed by members of the 115th Brigade 1st Battalion. “We are not alone like this, we are many.”

Ukraine’s military rebutted the volunteers’ claims in their own video posted online, saying the “deserters” had everything they needed to fight: “They thought they came for a vacation,” one service member said. “That’s why they left their positions.”

Hours after The Post interviewed Lapko and Khrus, members of Ukraine’s military security service arrived at their hotel and detained some of their men, accusing them of desertion.

The men contend that they were the ones who were deserted.

Waiting to die

Before the invasion, Lapko was a driller of oil and gas wells. Khrus bought and sold power tools. Both lived in the western city of Uzhhorod and joined the territorial defense forces, a civilian militia that sprang up after the invasion.

Lapko, built like a wrestler, was made a company commander in the 5th Separate Rifle Battalion, in charge of 120 men. The similarly burlyKhrus became a platoon commander under Lapko. All of their comrades were from western Ukraine. They were handed AK-47 rifles and given training that lasted less than a half-hour.

“We shot 30 bullets and then they said, ‘You can’t get more; too expensive,’ ” Lapko said.

They were given orders to head to the western city of Lviv. When they got there, they were ordered to go south and then east into Luhansk province in Donbas, portions of which were already under the control of Moscow-backed separatists and are now occupied by Russian forces. A couple dozen of his men refused to fight, Lapko said, and they were imprisoned.

The ones who stayed were based in the town of Lysychansk. From there, they were dispatched to Toshkivka, a front-line village bordering the separatist areas where the Russian forces were trying to advance. They were surprised when they got the orders.

When we were coming here, we were told that we were going to be in the third line on defense,” Lapko said. “Instead, we came to the zero line, the front line. We didn’t know where we were going.”

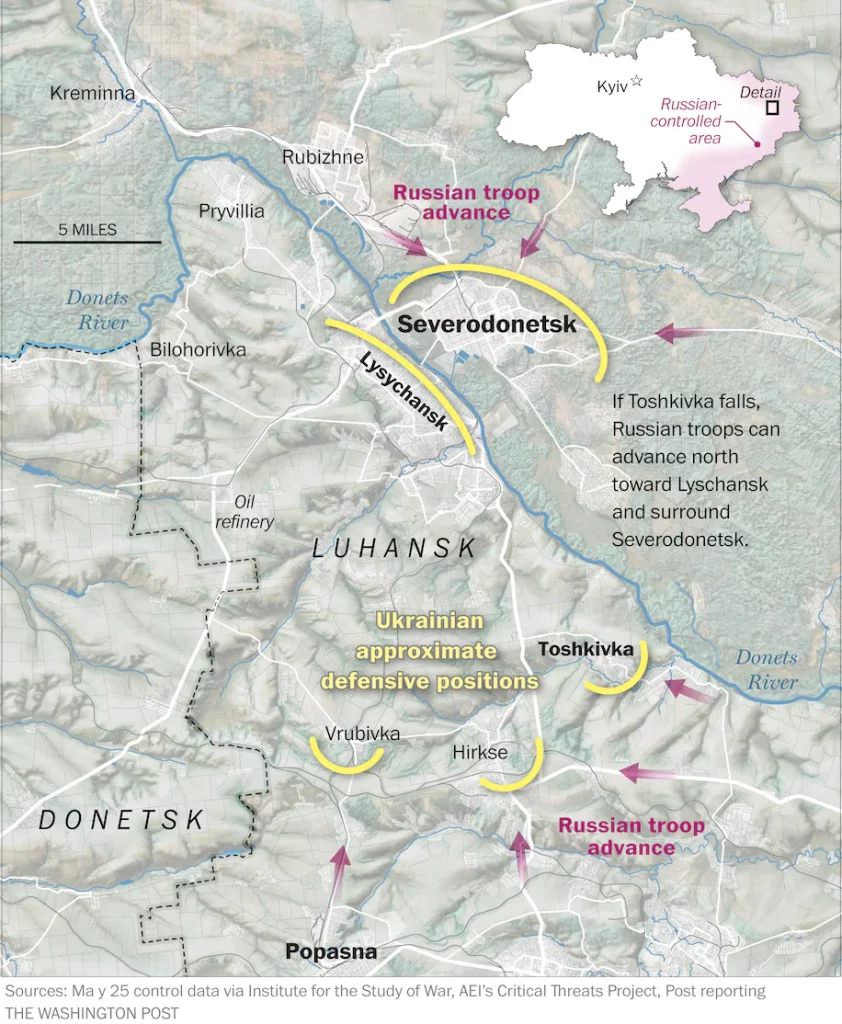

The area has become a focal point of the war, as Moscow concentrates its military might on capturing the region. The city of Severodonetsk, near Lysychansk, is surrounded on three sides by Russian forces. Over the weekend, they destroyed one of three bridges into the city, and they are constantly shelling the other two. Ukrainian troops inside Severodonetsk are fighting to prevent the Russians from completely encircling the city.

That’s also the mission of Lapko’s men. If Toshkivka falls, the Russians can advance north toward Lysychansk and completely surround Severodonetsk. That would also allow them to go after larger cities in the region.

When the volunteers first arrived, their rotations in and out of Toshkivka lasted three or four days. As the war intensified, they stayed for a week minimum, sometimes two. “Food gets delivered every day except for when there are shellings or the situation is bad,” Khrus said.

And in recent weeks, he said, the situation has gotten much worse. When their supply chains were cut off for two days by the bombardment, the men were forced to make do with a potato a day.

They spend most days and nights in trenches dug into the forest on the edges of Toshkivka or inside the basements of abandoned houses. “They have no water, nothing there,” Lapko said. “Only water that I bring them every other day.”

It’s a miracle the Russians haven’t pushed through their defensive line in Toshkivka, Khrus said as Lapko nodded. Besides their rifles and hand grenades, the only weapons they were given were a handful of rocket-propelled grenades to counter the well-equipped Russian forces. And no one showed Lapko’s men how to use the RPGs.

“We had no proper training,” Lapko said.

“It’s around four RPGs for 15 men,” Khrus said, shaking his head.

The Russians, he said, are deploying tanks, infantry fighting vehicles, Grad rockets and other forms of artillery — when they try to penetrate the forest with ground troops or infantry vehicles, they can easily get close enough “to kill.”

“The situation is controllable but difficult,” Khrus said. “And when the heavy weapons are against us, we don’t have anything to work with. We are helpless.”

Behind their positions, Ukrainian forces have tanks, artillery and mortars to back Lapko’s men and other units along the front. But when the tanks or mortars are fired, the Russians respond with Grad rockets, often in areas where Lapko’s men are taking cover. In some cases, his troops have found themselves with no artillery support.

This is, in part, because Lapko has not been provided a radio, he said. So there’s no contact with his superiors in Lysychansk, preventing him from calling for help.

The men accuse the Russians of using phosphorous bombs, incendiary weapons that are banned by international law if used against civilians.

“It explodes at 30 to 50 meters high and goes down slowly and burns everything,” Khrus said.

“Do you know what we have against phosphorous?” Lapko asked. “A glass of water, a piece of cloth to cover your mouth with!”

Both Lapko and Khrus expect to die at the front. That is why Lapko carries a pistol.

“It’s just a toy against them, but I have it so that if they take me I will shoot myself,” he said.

Survival

Despite the hardships, his men have fought courageously, Lapko said. Pointing at Khrus, he declared: “This guy here is a legend, a hero.” Khrus and his platoon, his commander said, have killed more than 50 Russian soldiers in close-up battles.

In a recent clash, he said, his men attacked two Russian armored vehicles carrying about 30 soldiers, ambushing them with grenades and guns.

“Their mistake was not to come behind us,” Lapko said. “If they would have done that, I wouldn’t be talking to you here now.”

Lapko has recommended 12 of his men for medals of valor, including two posthumously.

The war has taken a heavy toll on his company — as well as on other Ukrainian forces in the area. Two of his men were killed, among 20 fatalities in the battalion as a whole, and “many are wounded and in recovery now,” he said.

Then there are those who are traumatized and have not returned.

“Many got shell shock. I don’t know how to count them,” Lapko said.

The casualties here are largely kept secret to protect morale among troops and the general public.

“On Ukrainian TV we see that there are no losses,” Lapko said. “There’s no truth.”

Most deaths, he added, were because injured soldiers were not evacuated quickly enough, often waiting as long as 12 hours for transport to a military hospital in Lysychansk, 15 miles away. Sometimes, the men have to carry an injured soldier on a stretcher as far as two miles on foot to find a vehicle, Lapko said. Two vehicles assigned to his company never arrived, he said, and are being used instead by people at military headquarters.

“If I had a car and was told that my comrade is wounded somewhere, I’d come anytime and get him,” said Lapko, who used his own beat-up car to travel from Lysychansk to the hotel. “But I don’t have the necessary transport to get there.”

Retreat

Lapko and his men have grown increasingly frustrated and disillusioned with their superiors. His request for the awards has not been approved. His battalion commander demanded that he send 20 of his soldiers to another front line, which meant that he couldn’t rotate his men out from Toshkivka. He refused the order.

The final affront arrived last week when he arrived at military headquarters in Lysychansk after two weeks in Toshkivka. His battalion commander and team had moved to another town without informing him, he said, taking food, water and other supplies.

“They left us with no explanation,” Lapko said. “I think we were sent here to close a gap and no one cares if we live or die.”

So he, Khrus and several members of their company drove the 60 miles to Druzhkivka to stay in a hotel for a few days. “My guys wanted to wash themselves for the first time in a month,” Lapko said. “You know, hygiene! We don’t have it. We sleep in basements, on mattresses with rats running around.”

He and his men insisted that they want to return to the front.

“We’re ready to fight and we will keep on fighting,” Lapko said. “We will protect every meter of our country — but with adequate commandments and without unrealistic orders. I took an oath of allegiance to the Ukrainian people. We’re protecting Ukraine and we won’t let anyone in as long as we’re alive.”

But on Monday, Ukraine’s military security services arrived at the hotel and took Khrus and other members of his platoon to a detention center for two days, accusing them of desertion. Lapko was stripped of his command, according to an order reviewed by The Post. He is being held at the base in Lysychansk, his future uncertain.

Reached by phone Wednesday, he said two more of his men had been wounded on the front line.

Yevhen Semekhin contributed to this report.

https://www.washingtonpost.com