Nini Gabritchidze Jun 2, 2022

Following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, China-Europe cargo transport is shifting to the south, but infrastructure in the Caucasus is still relatively underdeveloped.

Europe-Asia cargo transportation through the Caucasus is growing manifold as international shippers seek to avoid Russia and hasten to set up new transit routes.

Cargo transshipment through Central Asia and the Caucasus will grow six times in 2022 compared to the previous year, to 3.2 million metric tons, according to the estimates of an association composed of the major state transportation companies in the region. “This is due to the sharply increased demand for the […] route against the backdrop of recent events taking place in the world,” the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route Association (TITR) wrote in a May 10 press release.

Russian Railways, which had played a major part in China-Europe cargo transportation, has fallen under American and European sanctions. On top of sanctions making it difficult to work with Russian companies, international shippers are uncertain about the current viability of that route. Others say they decided to ditch the route because of ethical considerations over Russian aggression against Ukraine.

In response, several international shippers have announced new initiatives in recent months redirecting transit to the south.

Danish shipping company Maersk in April launched a revamped rail service through the “Middle Corridor,” as the Central Asia-Caucasus route is often called. It said the route was launched “in response to customers’ ever-changing supply chain needs in the current extraordinary times.”

The first train to use the new service left Xi’an, China, on April 13, en route to Kazakhstan, the Caspian Sea, Azerbaijan, Georgia, and then across the Black Sea to Romania before arriving in Germany.

“In the current situation, this line is another alternative for logistics companies to stabilize exports,” Gia Min, manager of the international logistics company Ruiang in Xi’an, told Azerbaijan’s state news agency Azertac.

Finnish firm Nurminen Logistics on May 10 began operating a container train from China to Central Europe via the trans-Caspian route after designing the route “in two months from scratch.” Its first train reached Baku on May 27, before heading through the Caucasus and across the Black Sea before going to Finland.

And there are plans to add more freight ships in the Caspian Sea this year, Gaidar Abdikerimov, the Secretary General of TITR Association, said during a panel discussion in April.

Regional states also have been trying to stimulate the new trade routes. On March 31, the governments of Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Turkey signed a declaration on improving the transportation potential through the region. Georgia’s state railway company announced on May 25 that it was cooperating with companies from Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan to create a new shipping route using feeder vessels between ports in Georgia’s Poti and Constanta, in Romania.

The notion of using the trans-Caspian route as an alternative to Russia is not new. For decades, regional countries, along with the European Union, Turkey, and China have been trying to build up transportation routes throughout the region. The effort has continued to gain momentum with the rise of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

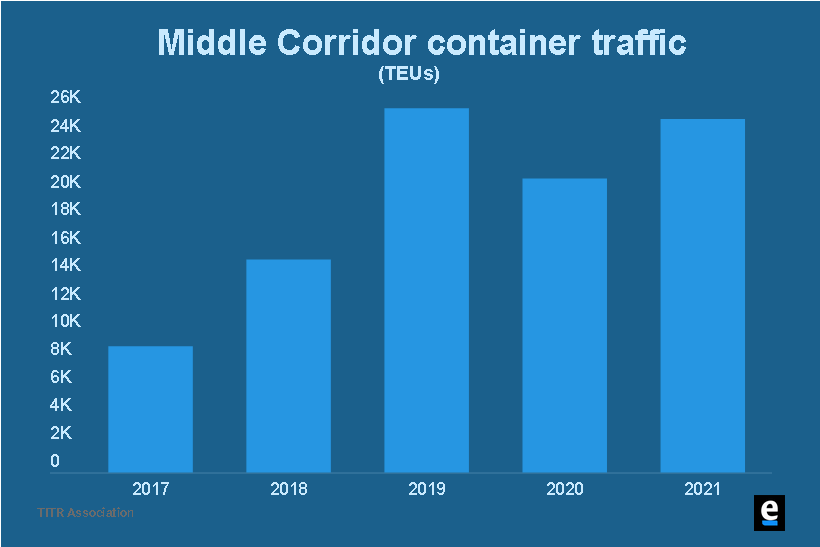

In 2017, the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railroad was launched, and transportation volumes have been growing steadily since, in spite of pandemic-related slowdowns.

But its capacity remains limited. “The corridor accounts for about 3-5 percent of the total capacity of northern routes,” Cankat Yildiz, an official from transport company Middle Corridor Logistics, told a panel discussion in March. “It’s a serious option, but this doesn’t mean that it can handle all the demand from the northern side. That’s clear.”

Because the route features several more border crossings than the Russian route, as well as the need for multimodal transfers to cross the sea, it costs more and is slower.

“The main problem with the corridor is that it involves slow and costly ferry legs to cross first the Caspian Sea and then the Black Sea from Georgia to the ports of Romania or Bulgaria or else utilizes an underdeveloped rail route through Turkey,” according to a 2021 report by the Asian Development Bank Institute.

As demand now shifts to the Middle Corridor, there are concerns in the Caucasus that the regional infrastructure is underprepared to handle the potential transportation bonanza.

“We, again, failed to prepare to meet all of this and, sadly, we are having some obstacles in this regard,” Givi Chachanidze, Georgian sales manager at Cosco Shipping Lines, a Chinese transportation company, told Business Media Georgia on May 12.

Among major infrastructure challenges that need to be addressed, Chachanidze cited the absence of a deepwater port on the Black Sea, the need for better railways, and the fact that the country’s major east-west highway has been under construction for years. Recent transportation demand has surpassed the Georgian railways’ capacity and some orders have had to be canceled, he said.

“We need to start this today, with every effort, this needs to become a national interest because our country is a country in need and this is like a gift that we need to grab,” Chachanidze said.

A decade-long major modernization of Georgia’s railways is expected to be completed this year, which will double its freight transportation capacity. But the Georgian government also two years ago controversially canceled the contract for the Anaklia deepwater port, which had been expected to play a key role in intercontinental transit. Tbilisi still claims that building the port remains a priority.

A dramatic increase in truck waiting times also has been reported at Georgia’s border crossings: On May 19, the Revenue Service of the Georgian Finance Ministry said all customs points were operating under a “special regime” due to “increased transportation freight turnover in the entire region.”

For Georgia, which for decades has tried to prove its strategic role to the West, its rising role in east-west transit is already good news.

But with increased transportation of goods through the country, it also stands to gain by growing trade relations with other countries along the corridor and cheaper import costs for staple goods, such as wheat. High transport costs for such goods have left Georgia dependent on the strategically risky Russian market, a situation that could be ameliorated should growing freight volumes decrease import costs from countries like Kazakhstan.

“This gives us a chance to attract, with the right moves, the volume of wheat through our corridor that could provide us with food security and become competitive with Russian wheat,” Giorgi Jakhutashvili, the chairman of the Kazakh-Georgian Economic Union, told Business Formula in April.

Azerbaijan, too, has long been trying to take advantage of international interest in the Middle Corridor. President Ilham Aliyev, in an April 2 letter to his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping marking the 30th anniversary of bilateral relations, singled out cooperation on transportation.

“Sitting at the crossroads of the east-west and north-south transportation corridors, Azerbaijan was among the first countries to support your ‘Belt and Road’ initiative,” Aliyev wrote. “The infrastructure projects implemented in our country in the transportation, transit and logistics areas and new corridors being made available usher excellent opportunities for our cooperation.”

Among the key projects is a Chinese-funded, $1.5 billion industrial park at Azerbaijan’s new Port of Baku at Alat.

The government may now be seeking to expand the capacity of the Port of Baku, currently 15 million metric tons of cargo annually, given the rising demand occasioned by Russia’s isolation. “Looking at the construction of Alat Economic Zone and other projects, these are attracting more international cargo shipping companies,” analyst Fuad Shahbaz told Eurasianet.

A delegation from Kazakhstan that visited Azerbaijan in May also appeared aimed at redirecting transit away from Russia and through the Caucasus, Shahbaz said.

Despite Aliyev’s warm words for Xi, however, there are several obstacles to Chinese transit through Azerbaijan.

“Azerbaijan has not yet fully committed to being a key part of China’s land-based trade and energy network,” the Carnegie Endowment wrote in 2021. “There are currently no agreements on currency swaps, industrial transfer, or free trade between the two countries, though China has concluded such agreements with Georgia and Armenia. On top of that, Azerbaijan has not shown any great enthusiasm for upgrading its old and slow railway infrastructure.”

With additional reporting from Heydar Isayev.

Nini Gabritchidze is a journalist based in Tbilisi.