The rise of Brenda Shaffer as a scholar and oft-quoted expert in the field of energy politics illustrates just how vulnerable the American foreign policy establishment is to manipulation by foreign agents.

Supported by an overseas regime and an assorted network of overt and undercover lobbyists, she used oil money to build her academic credentials, then in turn used those credentials to promote Azerbaijan’s agendas through Congressional testimony, dozens of newspaper op-eds and media appearances, countless think tank events, and even scholarly publications.

She’s still doing it.

Shaffer first walked into Congress in 2001 to testify before the House of Representatives’ Committee on International Relations.

She was introduced as “the director of the Caspian Studies Program and a post-doctoral fellow in the international security program at the Belfort [Belfer] Center for Science and International Affairs at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government”.

Addressing lawmakers, she asked them to repeal a section of the Freedom Support Act that barred direct US aid to the Azerbaijani government. “They have extended their hand to the US. They have huge expectations that the policy of this country is based on some sort of morality and high ideals,” she told them, and reinforced this in written testimony she also submitted.

Challenged about Azerbaijan’s democratic record, she replied: “There is a lot of room for improvement in terms of democratization. However, every six months, every year, things are getting better and better.”

What lawmakers listening to Shaffer didn’t know was that the Caspian Studies Program she headed at Harvard was set up in 1999 through a $1 million grant from the US Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce and a consortium of oil and gas companies led by Exxon, Mobil, and Chevron, all of which had commercial interests in the region. The chamber of commerce is a pro-Azerbaijan pressure group whose Board of Directors includes a vice president of SOCAR, the Azerbaijan state-owned energy company, and top lobbyists for BP and Chevron.

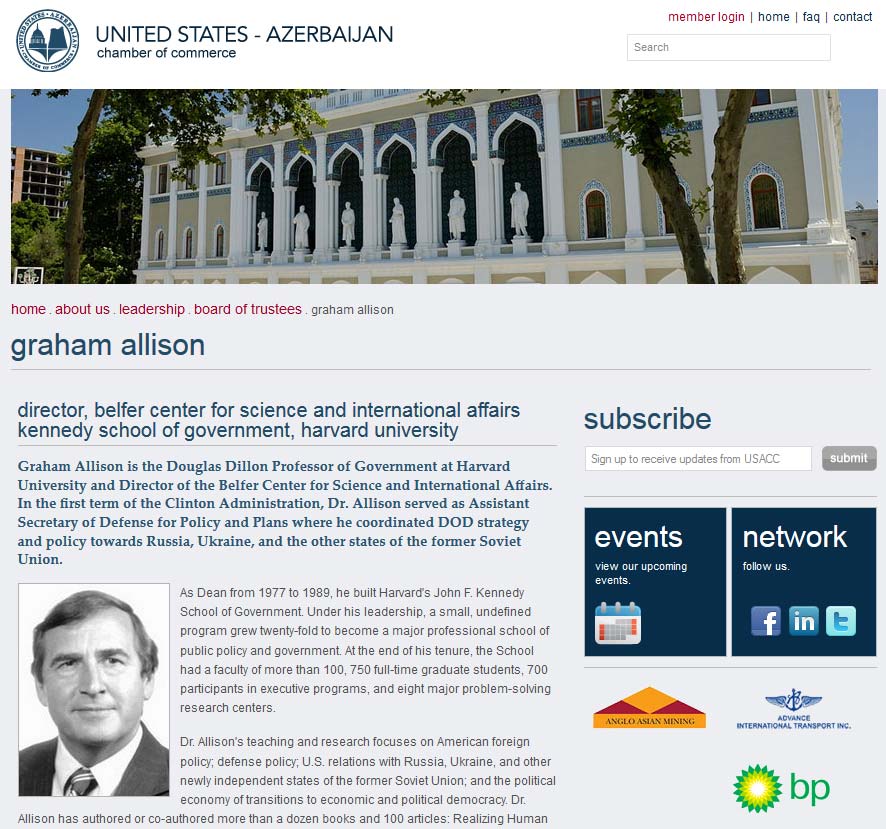

A 1999 press release from the chamber at the launch of the Caspian Studies Program noted its emphasis on outreach to “help to shape informed policy”. The Kennedy School of Government’s parallel press release announced that the program would open with a panel presentation and discussion chaired by Graham T. Allison and featuring Ilham Aliyev, then the first vice president of SOCAR. Allison was and remains the Director of the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, a prominent foreign policy think tank based at Harvard. Aliyev in 2003 succeeded his father as president of Azerbaijan.

Allison appointed Shaffer director of the new program in 1999 on the basis of merit, according to a Belfer Center spokesman, though the position was not advertised. The then-primary listserv for academic and policy-related jobs related to Eurasia, which was hosted at Harvard.edu, does not list any such vacancy related to the Caspian Studies Program.

At an event hosted by the Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce in 2000, Allison introduced Azerbaijan’s then-President Heydar Aliyev, who told his listeners that “I cheer the opening of a new chair at Harvard University relating to Azerbaijan and (the) Caspian area. I am thankful for the assistance of American-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce rendered for it.”

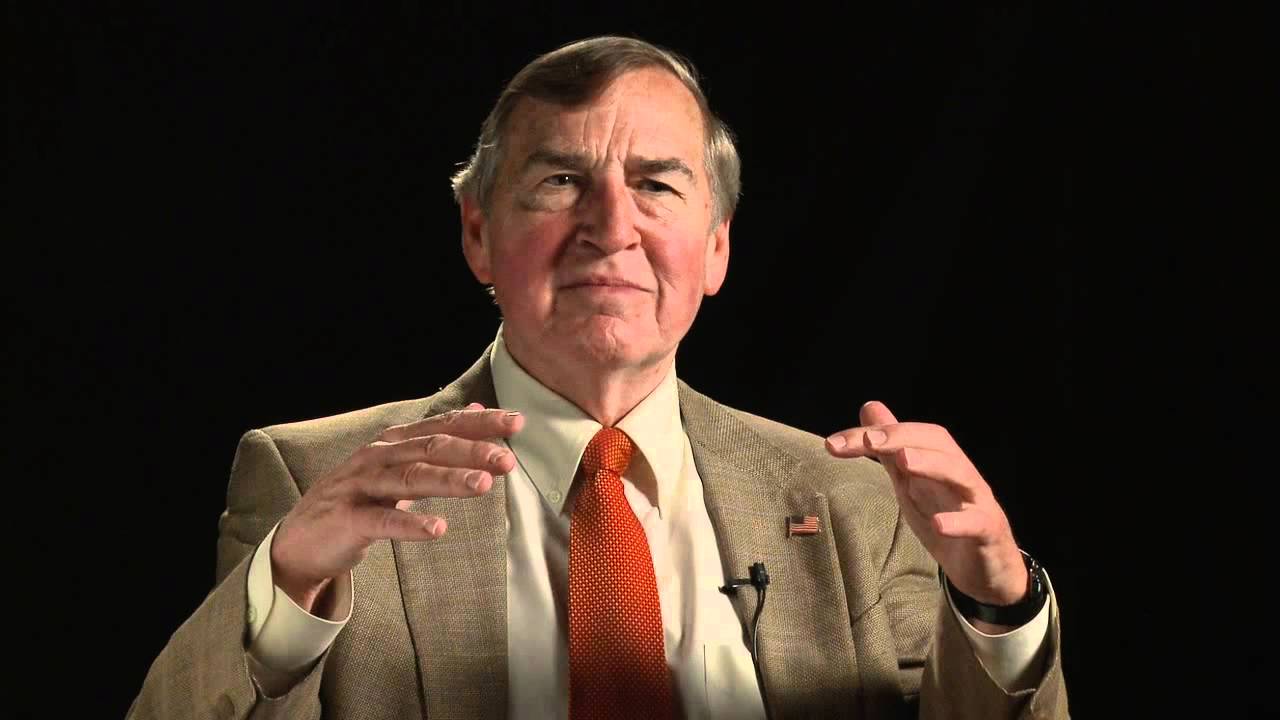

Until December 2014, Allison, the former dean of the Kennedy School, was listed online as a member of the chamber’s Board of Trustees. Graham Allison listed as a member of the Board of Trustees of the US-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce.

Graham Allison listed as a member of the Board of Trustees of the US-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce.

Questioned about the scholar’s relationship with the lobbying group, the Belfer Center spokesman replied that: “To the best of our knowledge, we had no awareness that Graham was listed as a member of the Board of Trustees of the US-Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce. After your note arrived, we contacted the chamber and asked them to remove Graham’s name. They have agreed to do so. Graham was never compensated for this apparently in-name-only role and he never, to the best of our knowledge, did any work on behalf of this organization.”

On the same day, the chamber removed Allison’s name from its website.

Further research revealed that the chamber’s supposed “Chairman Emeritus”, Dr Don Stacy, died several months ago.

It is unclear whether Henry Kissinger, Zbigniew Brzezinski, James A. Baker III, Brent Scowcroft and John Sununu are aware that they also are members of the group’s “Honorary Council of Advisors”, as the organization’s website claims. If so, it would make the chamber one of the best-connected foreign lobbying groups in D.C.

As a chamber of commerce, the Azerbaijan organization is incorporated as a 501(c)(6) non-profit, which allows it to conceal its donors from the public. In its 2011 tax filing, it reported paying more than US$ 100,000 in “other salaries and wages”, but without providing a breakdown of who received this money and for what. Neither its 2011 nor its 2012 filing report any direct expenditures for lobbying by external actors.

The chamber claims in its tax filings that it “makes its governing documents, and financial statements available to the public upon request”. Repeated requests for these documents emailed to its executive director, Susan Sadigova, went unanswered.

The Structure and Monitoring of Azerbaijani Lobbying Groups

Other Azerbaijani lobbying groups also prize confidentiality.

The Assembly of Friends of Azerbaijan, a heavyweight outfit with strong Congressional ties and traction, is also registered as a 501(c)(6), an IRS category intended to cover business leagues. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan America Alliance, an outfit chaired by former Indiana Rep. Dan Burton, is registered as a 501(c)(4) ‘social welfare organization’. This form of incorporation allows the Alliance to shield its donors from public view while it attempts to influence legislation and even participate in political campaigns and elections, including by supporting individual candidates.

Whether these groups need to register as “foreign agents” under US law is unclear. Azerbaijan America Alliance has formally registered. The Assembly of Friends has not, but says it will. The Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce has not registered, and there are no indications it plans to.

“Many non-profits are surprised to learn that there is no…exemption for non-profit, tax-exempt entities,” noted two legal experts following a 2010 scandal. “Penalties for failing to comply with… (lobbyist registration requirements) can include a fine of US$ 10,000 or imprisonment for up to five years.”

However, they hedge that it’s a challenge to figure out exactly what activities trigger the need to register, and that the Department of Justice gives little guidance about this.

Asked to comment on the specific case of the Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce, one expert, Ed Wilson, concluded that the organization is very probably not obliged to register under current rules.

Media Outlets Aided Shaffer’s Efforts for Azerbaijan

Shaffer led the Caspian Studies Program until 2005. During her tenure, she wrote 14 op-eds for leading US and Israeli newspapers including the International Herald Tribune and the Jerusalem Post. Most called on American policy makers to pay more attention to the region. One exhorted the US to stop funding for disputed Nagorno-Karabakh.

In May 2006, journalist and lobbying expert Ken Silverstein dropped a bombshell in the form of a short piece entitled “Academics for Hire” in Harper’s Magazine. It accused prominent academics of performing “intellectual acrobatics on behalf of the [Caspian] region’s rulers”. Shaffer was singled out for especially harsh criticism.

Silverstein highlighted the connection between Harvard and the Azerbaijan Chamber of Commerce, alleged that the Caspian Studies Program’s scholarship lacked intellectual integrity, and unearthed Shaffer’s 2001 plea to Congress to repeal sanctions against Azerbaijan.

He cautioned at the end of his article: “Caspian watchers beware: the next time you see or hear an ‘independent’ American expert talking about how the region’s rulers are implementing bold reforms, check the expert’s credentials to see just how independent he or she truly is.”

The next month, the International Herald Tribune ran its third Shaffer op-ed, about ethnic Azerbaijanis and other minorities in Iran. In the years since Silverstein outed her as an “academic for hire: whose career was fuelled by Azerbaijani lobbying outfits and Western oil companies invested in Azerbaijan,“ Shaffer has placed 13 additional op-eds, 10 of these in American outlets.

Did the editors of America’s opinion pages not know about Shaffer’s reputation, or not care?

I emailed to the New York Times, Washington Post, Reuters, and Wall Street Journal a link to the article that broke the story, asked them to explain how they screened op-ed contributors, and encouraged them to publish a clarification beneath Shaffer’s op-eds, all of which were still online.

The Times quickly posted a clarification that said: “This Op-Ed, about tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan, did not disclose that the writer has been an adviser to Azerbaijan’s state-run oil company. Like other Op-Ed contributors, the writer, Brenda Shaffer, signed a contract obliging her to disclose conflicts of interest, actual or potential. Had editors been aware of her ties to the company, they would have insisted on disclosure.”

Michael Larabee, the Op-ed Editor at the Post, responded that, “We make inquiries about possible conflicts of interest with all writers prior to publication.” The Post also published a clarification.

Reuters ran three op-eds by Shaffer in 2013. Two identified her as a visiting researcher at Georgetown and a University of Haifa professor. The third stated simply that, “The author is a Reuters columnist. The opinions expressed are her own.”

One of these op-eds advised US policy makers on how to handle Syria. Even though Syria and Israel are technically in a state of war, readers were not informed that the author was the member of an Israeli government steering committee.

Reuters also ran a Shaffer piece about Azerbaijan’s human rights record. Baku’s regime persecutes its critics mercilessly; democracy activists routinely get beaten up or thrown into jail on patently absurd charges. In 2013 alone, the State Department reported, the list of human rights violations in Azerbaijan included beating military conscripts to death, torture (including threats of rape) to coerce confessions, and detention conditions that were sometimes “life threatening”.

“Protection of human rights is not necessarily better under illiberal elected regimes… Many new populist governments do not support the rights of women and minorities…” Shaffer offered an alternative perspective.

Reuters declined to add a clarification about Shaffer’s outside interests.

Her opinion piece in the Journal simultaneously took a swipe at Palestine and discouraged US support for Azerbaijan’s rival Armenia in the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute.

Judi Walsh, the paper’s News Editor, Newsroom Standards, notified me that my email requesting a reaction had been passed on to the paper’s Editorial Department, which – she wrote – had been “responsible” for disseminating Shaffer’s op-ed.

No correction was published. Instead, last Nov. 30, the Journal posted another Shaffer op-ed online, identifying her as “a visiting researcher and professor at Georgetown University’s Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies.”

Other media outlets continue to cite Shaffer as an independent expert. Bloomberg’s Businessweek ran a story quoting her, without mentioning her link with SOCAR, praising Azerbaijan’s dependability as an oil supplier. “Azerbaijan is very serious about the sanctity of contracts,” she told Businessweek. “It has never reopened its international contracts in the energy sector.”

The responsible editor, Hellmuth Tromm, did not reply to an email requesting an explanation, and the article remains online in its original version.

Veteran journalists Jackie Northam from National Public Radio and Roger Boyes from the London Times have also recently quoted Shaffer.

Think Tanks

In addition to writing op-eds and advising SOCAR, Shaffer over the years has run many laps around the D.C. think tank circuit.

Her participation in a 2013 panel discussion at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace about Azerbaijan’s prospects is a case in point.

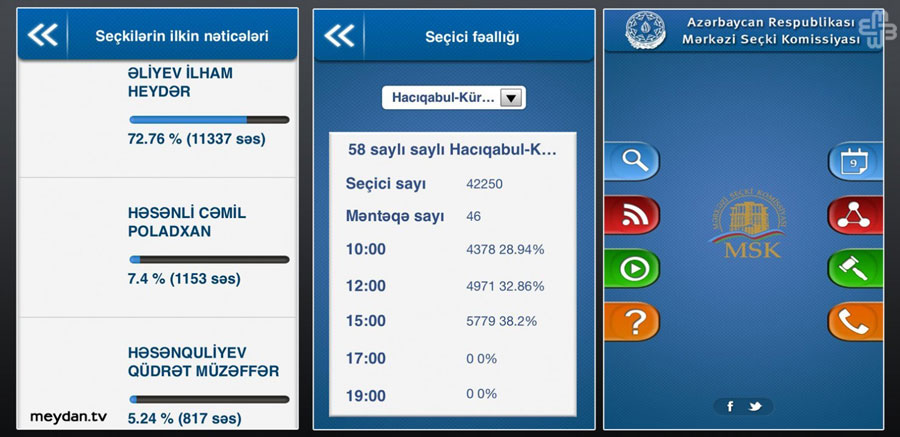

The panel took place two days after the 2013 elections in Azerbaijan, which had been comical. The election commission accidentally released the final results a day before polling had begun. Otherwise, there were no surprises: Ilham Aliyev, the incumbent, won by a large margin.

According to an official U.S. State Department report, “Flaws in the conduct of the… presidential election included a repressive political environment leading up to election day, lack of a level playing field among candidates, [and] significant shortcomings throughout all stages of election-day processes.”

Shaffer told her audience at Carnegie, according to an audio recording of the event, that the very fact that so much was known about electoral and other abuses in Azerbaijan demonstrated just how open a society it was.

She praised Azerbaijan’s “vibrant press”, its fierce political debates, and its “realistic” voters. She expressed hope that with elections over, Azerbaijan would take “even more bolder steps towards democracy. It will do a better job… if it has the US on its side… If you really care about democracy in Azerbaijan… be a partner there, be a friend there.”

Prof. Donald Abelson from the University of Western Ontario, an expert on think tanks, says policy shops can have reasons for hosting experts whose neutrality is questionable: “First, “ he said, “their presence could help to highlight the independent posture of the host relative to the more biased guests… Alternatively, the think tank inviting these people might simply want them there to create controversy or generate media attention. Or, it’s possible that they are there for whatever expertise they possess.”

However, in contrast to much of the US media, some think tanks distanced themselves from Shaffer once her SOCAR connection became known. The Wilson Center, which lists her as an expert on its website, explained in an email: “The way that our website lists people can be misleading… Ms. Shaffer has no Wilson Center affiliation.”

She still, however, gets her voice heard. At least two think tanks have recently posted contributions by her online – identifying her only as an academic expert.

The Role of Academia in Foreign Affairs Formulation

The academic institutions that have lent Shaffer credibility over the years continue to support her. Foreign Affairs journal, noted for its strong influence among policy-makers, published a contribution by Shaffer that discussed a proposed pipeline to carry gas from Azerbaijan to Europe as follows: “[I]t will edge out coal once more and help lower pollution and carbon emissions… Europe’s efforts to increase eastern pipeline gas are a good start toward addressing the continent’s energy woes… And hopefully the United States will hold off on fast-tracking exports until the benefit of those extra supplies for Europe becomes clearer.”

The journal’s editor did not respond to emails pointing out Shaffer’s apparent conflict of interest and asking for a reaction.

When Shaffer’s side job in Baku first became public, the reporter who broke the story publicly challenged Georgetown University’s Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies via a Twitter campaign to disclose her SOCAR affiliation.

Georgetown never reacted, and Shaffer’s profile page there continues to make no reference to her commercial interests. The school also has recently added an “In the news” section to her profile that showcases her latest public commentary. During December 2014 alone, Shaffer appeared on TV screens via Fox Business and Al Jazeera America, and commented on energy issues in print via the Jerusalem Post, London Times, The Australian, NPR, and Foreign Policy magazine. (Only weeks earlier, Foreign Policy itself had run a piece on Azerbaijan’s lobbying efforts by a different author that mentioned Shaffer’s SOCAR connection.)

Some academics caution that external funding need not compromise independent scholarship. UK-based Prof. Timothy Edmunds, editor in chief of the European Journal of International Security, said: “Many academics have ‘outside’ funding. The question is when that line is crossed to having outside interests. I think these are questions of professional responsibility and integrity, though transparency in declaring interests (and proper sanction against those who don’t) is also key.”

Shaffer denies crossing the line from outside funding to outside interests.

During an October 2014 public discussion at Columbia University during which she shared the podium with an official SOCAR representative, a participant asked Shaffer about her links with the state-owned energy company, and whether Congress had been aware of that relationship when she testified. In a testy exchange, Shaffer insisted that her scholarly independence had not been compromised, and that “my students benefit from the fact that I have been on every side of the table.”

In email exchanges, several regional experts reported having detected bias in Shaffer’s output in the past. “Scholars in academia do not regard her work as really academic,” wrote Manouchehr Shiva, who did research in Azerbaijan under a Fulbright scholarship in 2005-2006 and continues to follow developments there.

Should Georgetown have been more cautious about inviting the SOCAR advisor on board?

“The sponsoring institution has a responsibility to prevent cases like Shaffer’s,” said Gerald Robbins of the Foreign Policy Research Institute. At the same time, he cautioned, “Due diligence is a challenging feat when confronting such matters as academic tenure and intellectual freedom. Inevitably it’s an ethical issue where checks and balances would have questionable impact.”

Furthermore, Shaffer does have genuine and strong academic credibility markers to her name: books published at university presses, articles in respected peer-reviewed journals, and active membership in an academic association. While some of her books have been very critically received, this in itself should not raise any red flags.

Ironically, just as her academic titles facilitated her getting op-eds in major newspapers, those media pieces, in turn, strengthened Shaffer’s academic credentials. The same feedback loop seems to apply to Congressional appearances. The first time she appeared in front of Congress in 2001, lawmakers were told that “Dr. Shaffer’s op-eds have appeared also in the International Herald Tribune and the Boston Globe.”

To sum up: SOCAR funded a programme at Harvard that furnished Shaffer with an impressive academic title, which in turn opened doors to the media, which in turn – maybe with a little help from Azerbaijan’s friends on the inside – opened doors to Congress.

Closing the loop, the homepage of her department at Georgetown contains a prominent link to the latest Congressional testimony by “CERES Visiting Researcher Shaffer”, and her profile page lists all her op-eds and recent media appearances, while the Georgetown University page titled “Media: Find a Subject Matter Expert” encourages journalists who type in “Azerbaijan” or “energy” to contact Brenda Shaffer for commentary.

It seems that in D.C., each lap around the policy circle of media, think tanks, academia, and politics further builds credibility, but nobody is checking credentials along the way.Tweet this

How to Build Yourself a Stealth Lobbyist, Azerbaijani style – Corruptistan (occrp.org)